Types of Wildland Fire

By Louisa Evers, Golden Eagle Audubon Board Member

Wildland fires carry more than sparks and smoke—they carry definitions that matter. Before you click “play” on the next big blaze headline, it’s worth noting how a fire is burning and how it behaves aren’t the same as how hard it hits the landscape. In the wildland-fire world, “intensity” refers to the immediate energy release, and “severity” describes the aftermath. To get clear on what’s happening in the woods, let’s start with the classification of fire types.

Wildland fires are categorized based on where they burn, the direction they spread, and how intense they become. Many older research papers—and even today’s media—often mix up the terms fire intensity and fire severity, describing fires as “hot” or “cool,” or calling them “intense” when they mean severe. Fire intensity (or fireline intensity) measures the energy a fire releases, expressed in British Thermal Units (BTUs) or kilowatts per minute (kW/min). In the field, flame length serves as a practical indicator of this energy, and intensity can also be calculated through fire behavior models. Fire severity refers to the fire’s impact—for example, how many trees are killed or how much habitat quality changes. In short, intensity describes what happens during the fire, while severity describes what’s left after the fire is out.

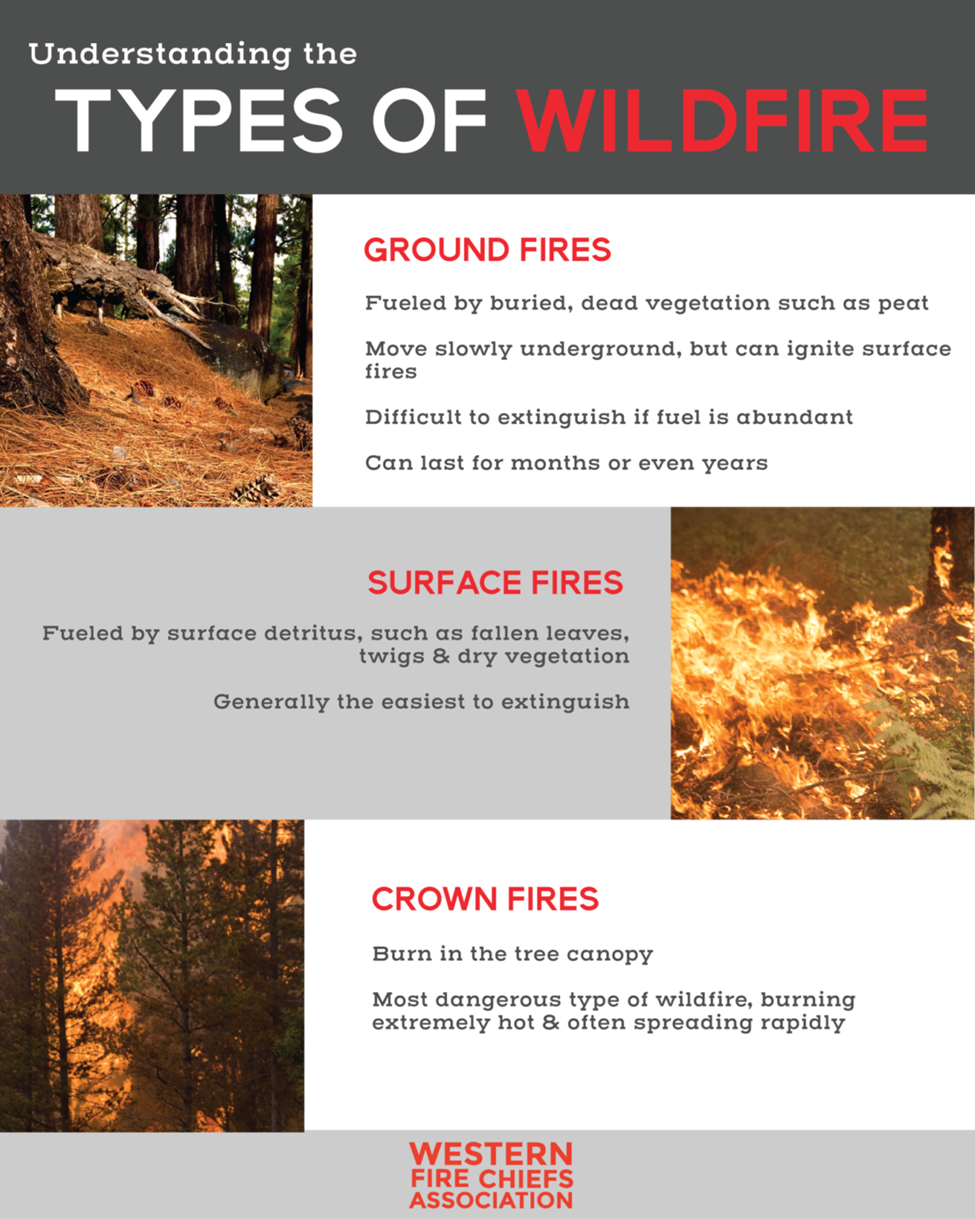

Where the Fire is Burning

Fires burn in three different locations, although only two are common in Idaho.

Peat fire in Canada

Surface fire in pine stand

Crown fire in conifer forest

Ground Fire

A ground fire burns below the ground surface in organic fuel such as peat, very deep forest duff, or roots. These fires are much less common in Idaho. They can break through to the surface and start a surface fire, and smoke often escapes through the surface. Burning coal seams are another type of ground fire and have started surface fires in Colorado and Pennsylvania. Fires can spread through large tree roots and resurface outside the fireline, so extinguishing all root holes near the fireline is necessary.

Surface Fire

A surface fire spreads on the ground surface, usually in fine fuels such as grass, litter, thin duff layers, shrubs, and small trees. A surface fire is the most common fire type and is responsible for the majority of fire spread. The flames are visible, and a fireline is intended to stop the spread of a surface fire. The news media and those not familiar with fire terminology may mistakenly call a surface fire a ground fire.

Crown Fire

A crown fire spreads through tree canopies and the canopies of tall shrubs. Crown fires are usually ignited by a surface fire. The fuels in a crown fire include live foliage, dead branches and twigs, and lichens and mosses. The canopy may or may not have vertical continuity with the surface fuels, so factors such as flame length and slope steepness—which can increase the effective flame length—become important to the initiation and spread of a crown fire. There are several types of crown fires, which I will cover under Fire Intensity.

The Direction of Fire Spread

A fire has distinct areas: the head, flanks, and rear.

Head Fire: This is the leading edge of the fire, spreading with the wind and slope. It has the fastest rate of spread and usually has the greatest flame length, making it the most dangerous part of the fire.

Flank Fire: This fire spreads at roughly 90 degrees to the direction of the wind along the sides of the fire. Flank fires cause the fire to get wider and can increase the size of the fire head. Dry cold fronts can cause the flank fire to become the head as the wind changes direction.

Backing Fire: This fire spreads against the wind at the rear of the fire. Backing fires have the slowest rate of spread and lowest flame length. However, under certain conditions—such as steep slopes, strong winds, or fuel type—a backing fire can spread more quickly, though it still maintains the lowest flame length.

Whenever possible, firefighters prefer to start constructing fireline at the rear of the fire to stop it from backing and work their way up the flanks, eventually pinching off the head.

Wildland fire behavior hauling chart

Fire Intensity

Fire intensity refers to the energy released by the fire and is usually indicated by flame length and other fire behavior characteristics such as rate of spread and spotting distance. Spotting occurs when burning material is lifted into the air and lands beyond the main fire, starting additional fires. Firefighters use a tool known as the Hauling Chart to indicate actual or potential fire intensity.

Fireline construction methods vary depending on the intensity of the fire, as indicated by flame length:

Flame Length < 4 feet: Hand crews can construct fireline directly on the fire's edge using hand tools.

Flame Length 4–8 feet: Mechanical equipment, such as bulldozers, is required to construct fireline.

Flame Length 8–11 feet: Crown fire behavior is likely, indicating a significant increase in fire intensity.

Flame Length > 11 feet: Expect crown fire, rapid fire spread, and long-distance spotting.

These guidelines help determine appropriate firefighting tactics and resource allocation.

Crown Fire Types

There are three types of crown fire: passive, active, and independent.

A passive crown fire occurs when individual trees or small groups of trees ignite and burn—commonly referred to as "tree torching." This type of fire produces limited burning material, which is typically small and carried only a short distance, usually just a few feet away. Whether spot fires start depends on fuel dryness and whether the material burns long enough upon landing to ignite new fires.

An active crown fire develops when the fire spreads from crown to crown over a significant distance, often burning several acres. These fires, sometimes called "running crown fires," produce substantial amounts of burning material, which is larger in size and carried further, leading to multiple spot fires up to ½ mile away. However, most spot fires occur within ¼ mile of the main fire. Both passive and active crown fires are dependent on the energy generated by the surface fire, so they spread at roughly the same rate. An active crown fire may surge ahead of the surface fire but must "wait" for the surface fire to catch up; otherwise, it drops back down and becomes a surface fire again.

Single tree torching

Active crown fire

An independent crown fire is the rarest and most dangerous type of crown fire. Unlike other crown fires, it does not rely on the energy of the surface fire. Instead, it is fueled by the energy generated within the burning canopy itself. This type of fire can advance rapidly, often outpacing the surface fire, and can produce significant amounts of burning material that is lofted ahead of the main fire. The spread direction and rate of an independent crown fire are highly unpredictable, making it particularly hazardous.

Firefighting Tactics

Firefighters cannot directly combat crown fires. They must wait for a change in fuels or weather to bring the primary fire down to the surface. However, actions such as retardant and water drops are often employed to reduce some of the heat and energy from the crown fire, attempting to force it back to the surface. The success rate of these actions is highly variable.

Firefighters may also use indirect firefighting tactics, such as backfiring (igniting a fire at a distance from the main fire), to alter the fuels sufficiently to cause the crown fire to drop back to the surface or even stop. Backfiring is a risky tactic because determining the appropriate distance to start the backfire is challenging, and predicting whether the backfire will slow or stop the main fire is difficult, especially when the fire is producing numerous spot fires over long distances. Additionally, preparing for a backfire typically requires several days to construct the necessary fireline to control it. Changes in weather conditions or fuel availability can render the backfire unnecessary or ineffective, making it a complex and uncertain strategy.

In Conclusion

Understanding the dynamics of fire behavior—how it burns, spreads, and transitions between layers—transforms vague terms like "hot" or "intense" into precise knowledge. This knowledge is crucial for effective fire response, ecosystem recovery, and public safety. Whether a fire is smoldering underground, racing through towering treetops, or flanking across slopes, each scenario demands specific strategies and awareness. By grasping these distinctions, we equip ourselves, our communities, and our firefighters with the strategies and awareness to respond more effectively. This knowledge just might make the difference the next time fire takes the stage.

Editor’s Note: Louisa has a professional background in fire ecology and many years experience assessing fire risk and predicting fire behavior. Read her previous blogs for more information.